Cyd Charisse could do it all—sing, act, and, above all, dance like music made flesh. Her impossibly long legs became the stuff of Hollywood legend, yet she began life not as a star but as Tula Ellice Finklea, a sickly Texas girl recovering from polio. Doctors recommended ballet as therapy to strengthen her fragile body. What began as rehabilitation became destiny. The little girl who once struggled to walk grew into a woman who made movement eternal. A brother’s playful mispronunciation of “Sis” became “Cyd,” and soon Hollywood did the rest.

She grew up in Amarillo, a place where dust storms outnumbered spotlights and glamour felt as far away as the moon. Ballet, however, reshaped her body and spirit, transforming illness into artistry. By her teenage years she had moved beyond Texas, studying in Los Angeles and even abroad with Russian masters. For a time she performed under Russian-sounding names, a nod to ballet’s traditions, but the essence was always uniquely hers: cool elegance fused with fierce musicality.

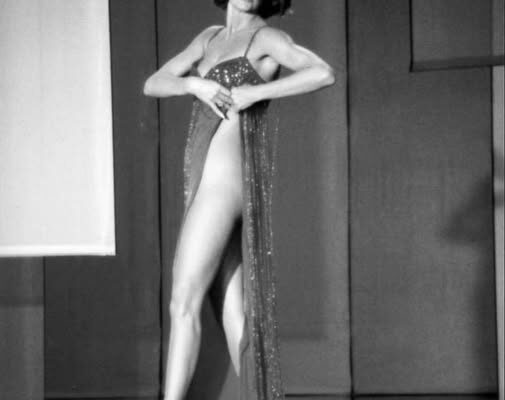

Film discovered her through dance rather than dialogue. Charisse’s beauty was undeniable, but it was her ability to let choreography speak that caught Hollywood’s attention. MGM, then the dream factory at its golden height, signed her. Slowly she moved from background dancer to featured performer, and by 1952 she was unforgettable in the “Broadway Melody” ballet of Singin’ in the Rain. Draped in a green dress that shimmered like envy itself, she delivered seduction and danger without uttering a single word. One glance, one extension of those endless legs, said more than dialogue ever could.

What made Charisse rare was her ability to shine opposite both Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire—two men who defined cinematic dance in utterly different ways. With Kelly she was silk wrapped around steel, a match for his athletic, muscular style. With Astaire she became the perfect partner, breathing phrasing into every step, turning technique into poetry. Their duet “Dancing in the Dark” from The Band Wagon (1953) remains one of the great screen romances, not for plot but for inevitability: two people waltzing as if the world had always meant for them to find each other.

Her genius was never just the legendary legs, though those photographs endure. It was her phrasing, her way of sculpting time. Ballet had given her line and carriage, yet she knew how to bend those classical shapes into jazz, modern, or pure Broadway. Where other dancers dazzled with speed, Charisse enchanted by slowing down—stretching a phrase, suspending it in air, then snapping it tight like silk pulled taut. She made rhythm visible.

MGM kept her endlessly busy. She brought danger to Singin’ in the Rain, sophistication to The Band Wagon, wit to Silk Stockings (1957), and allure to Party Girl (1958). Offscreen, she was strikingly unlike her screen sirens: punctual, professional, and private. She built a grounded home life with singer Tony Martin, her husband for sixty years, a rare Hollywood love story that endured longer than the studio system itself.

Her life, however, was not untouched by tragedy. In 1979, her daughter-in-law was killed in the crash of American Airlines Flight 191, one of the deadliest air disasters in U.S. history. Charisse carried on with quiet dignity, later returning to the stage and mentoring younger dancers who sought her wisdom. Recognition came late but fittingly: in 2006 she received the National Medal of Arts, a testament to her cultural impact.

Charisse died in 2008, but her films continue to hum with life. Watch The Band Wagon and feel an ordinary park transform into a ballroom. Cue Singin’ in the Rain and see that green dress blaze across memory. Her language was movement, her vocabulary limitless. Long after words fade, Cyd Charisse’s legacy still dances.